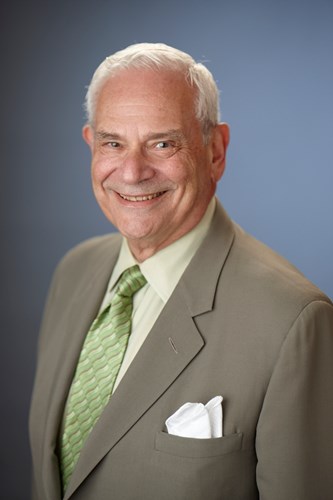

The Big Interview...Elkan Abramowitz

Why did you decide to become a lawyer?

Why did you decide to become a lawyer?

In my Brooklyn neighborhood there were really only three career options: the law, medicine, and going into business with your father. My father was an accountant and I couldn’t add two and two, so I really thought I couldn't be an accountant. Also, I couldn't stand the sight of blood. So by default, I just kept saying I was going to be a lawyer. Despite briefly fancying the idea of becoming a high school teacher, I have been dedicated to law.

Starting out, what did you expect from a career in law?

Early on, I viewed myself as being very shy. I did not know that I had the chops to be a trial lawyer. However, after my summer job in the US Attorney’s office, followed by a District Court clerkship right out of NYU Law, everything changed (including my expectations). Watching the trial work of the great trial lawyers of the day reassured me that I was cut out to follow in their footsteps.

"Trying white collar cases has evolved into an exercise as to which side has the more significant electronic evidence."

How did you get into white collar defense? By design? By chance?

I went to law school before trial-practice courses were offered, so I had to learn from other ways. During my clerkship in the S.D.N.Y., I watched and learned from really good trial lawyers on both sides, and I realized this is something I really could be competent doing. I learned by watching, as opposed to doing. I also noted what came naturally to me as well as what skills of mine might need sharpening. With the skills I learned in the US Attorney’s Office, it was natural for me to specialize in white collar defense.

You took a lot of cases to trial very early on in your career. What do you consider to have been your big break?

Yes, I tried 30 cases to verdict before I was 30, which certainly kick-started my career. In 1976 when US Attorney Bob Fiske asked me to return to the government as Chief of the Criminal Division I accepted his offer, solidifying another pivotal milestone. He wanted someone with defense experience, which is a perspective that I wish more career prosecutors understood.

What’s been the most eye-opening experience of your career and what has it taught you?

Trying white collar cases has evolved into an exercise as to which side has the more significant electronic evidence. Instead of cases involving just oral testimony, too many cases now rely on ill-conceived emails which are expensive to retrieve and sometimes difficult to explain.

What single achievement are you most proud of?

I am extremely proud of my recent representation of Steven Davis, the former Chairman of Dewey & LeBoeuf, and the related marathon trial. Indeed, the trial was referred to as the legal industry’s trial of the year. It centered around allegations that Davis and two other executives engaged in a long-running scheme to defraud investors. But prosecutors failed to tell a coherent story, which allowed me and my team to prove that there was no crime. Once you really believe that – and I did believe it before the trial – all your cross-examinations and all your openings and summations fall into place.

What do you consider your greatest failure or regret?

Not trying more cases. Because of the sentencing guidelines and the expense and complexity of modern white collar prosecutions, fewer and fewer cases are going to trial. This ends up giving the government too much power in defining what is criminal conduct. In my view, we need more juries to intervene in reviewing the government’s judgment.

"How best to deal with business activity that damages the public good? I stand by my conviction that prosecuting CEOs is generally not the answer."

What have you enjoyed most during your career in the legal profession?

Reflecting on my career, I am particularly proud of my defense work involving prosecutions that, I believe, have represented misguided efforts to address an important national policy question: how best to deal with business activity that damages the public good? I stand by my conviction that prosecuting CEOs is generally not the answer.

And the least?

The drudgery of discovery in civil cases.

What do you want your legacy to be?

A dedicated family man who had the courage and support to navigate and conquer a challenging area of the law.

What law would you change, abolish or create?

The question of guilt or innocence is something that is not so stark in white collar cases because often the problem is not whether somebody did something, but whether what they did was knowingly wrong. There's no question that what went on in the financial crisis was a disaster on every level, but the answer is not to stretch traditional notions of criminality to try to put people in jail. The answer is to create a regulatory environment where these things can't happen again. I firmly believe that the clamor to prosecute the bankers of the 2008 stock market collapse is unwarranted. The public’s focus on senior executives deflects attention from the core issue – poorly regulated financial instruments.

"The problem is not whether somebody did something, but whether what they did was knowingly wrong."

Who is your legal hero?

I’ve had three bosses in my career: Inzer B. Wyatt, Robert M. Morgenthau, and Robert B. Fiske, all of whom are my legal heroes. I learned the importance of scholarship, precision, compassion, thoroughness, craftsmanship, and integrity – things that I hope are reflected in my work to this day.

What differences do you see in today’s legal market compared to when you started?

When I started out, white collar law was less ubiquitous. Today, white collar law has become a standard practice area in Biglaw. The other significant change is the globalization of law firms, which have increased exponentially in size. Unfortunately, our profession is still struggling with diversity and inclusion.

What advice would you give to students trying to enter the legal profession today?

Work hard, evaluate your strengths and weaknesses, and pursue opportunities of interest.

And to those looking to become a trial lawyer?

Trial practice is not for everyone, but if you find your way to the first chair remember my most important trial motto: KISS (keep it simple stupid), followed by one of my favorite courtroom rules: when you’re winning the argument with the Court, stop speaking. Sometimes the more you argue, the more you might convince the Court that it was wrong in initially agreeing with you.