It's A Wonderful Life is only two hours long - here's our pick of the films law students should watch during the rest of the holidays...

Around this time of year – as the wintry winds usher in a period of rest, respite and revelry – we can barely contain our excitement. We're not gloating; we're more than aware that many of you are still stumbling over statutes and trembling under teetering towers of textbooks. But please – we must insist – take a break on us.

For the team here at Chambers Associate, there's nothing better than using this time to take in a bit of cinema. If it features the Wet Bandits or John McClane – great. If it makes us think again about law and society – even better. Since we're a precocious bunch of culture vultures, and since it's a season for giving, what better gift than yet another watch list for the festive period?

(If books are more your thing – we've got a list for that too, as picked by BigLaw partners)

But we're taking a stand against cliché this year. No more Legally Blonde (as much as we love it). Step forward our (self-elected) film buff Joel Poultney – he's on a mission to drench your holiday film selections in a less-than-festive, but definitely thought-provoking eggnog. Enough of that image – here are seven films that cast light on the power of truth, the rule of law, and how justice in cinema moves beyond the confines of the court.

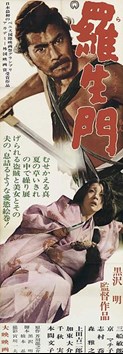

Akira Kurosawa's Rashomon (1950)

Seeking refuge from the rain, a woodcutter, a priest, and a weary traveler find shelter under a dilapidated city gate. It might sound like the set up for an old joke, but what transpires is neither comical nor irreverent. Instead, Kurosawa's allegorical tale is routinely tipped as one of the greatest films ever released. In a profound and discomforting nod to the virtues of truth, four witnesses provide contradictory accounts of a horrendous crime. Though the testimonies form part of a court hearing, we never see the hearing's completion. Instead we, as audience members, sit among the jury, clawing at the kernels of truth to determine our own understanding of events.

Seeking refuge from the rain, a woodcutter, a priest, and a weary traveler find shelter under a dilapidated city gate. It might sound like the set up for an old joke, but what transpires is neither comical nor irreverent. Instead, Kurosawa's allegorical tale is routinely tipped as one of the greatest films ever released. In a profound and discomforting nod to the virtues of truth, four witnesses provide contradictory accounts of a horrendous crime. Though the testimonies form part of a court hearing, we never see the hearing's completion. Instead we, as audience members, sit among the jury, clawing at the kernels of truth to determine our own understanding of events.

<--- Japanese re-release poster shown, featuring Toshirō Mifune and Machiko Kyō

The film's central arrangement – the witnesses' multiple manipulations of reality – even coined a term: 'The Rashomon effect.' Rightly so. It's Kurosawa's acute examination of the desire for objectivity and the pursuit of truth that continues to make this film so wonderful after all these years.

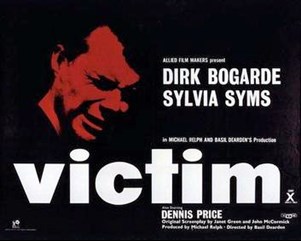

Basil Dearden's Victim (1961)

Cloaked under the guise of a conventional thriller, Basil Dearden's perceptive depiction of a respected barrister who becomes embroiled in a web of deceit and blackmail feels alien to our contemporary worldview. Yet, for the people it portrayed, it is an all-too-real reminder of an era in which homosexuality remained both obscene and illegal. Dirk Bogarde gives an extraordinary performance as Melville Farr, a compromised QC-in-waiting, as he navigates the murky streets of London, held captive by a photograph of him and a would-be lover crying together in a car. What's remarkable about the film is how, for the first time, it brought such a compassionate and tender representation of homosexuality to British screens; showcasing gay men as victims of a punitive law, rather than criminals seeking to thwart it.

Cloaked under the guise of a conventional thriller, Basil Dearden's perceptive depiction of a respected barrister who becomes embroiled in a web of deceit and blackmail feels alien to our contemporary worldview. Yet, for the people it portrayed, it is an all-too-real reminder of an era in which homosexuality remained both obscene and illegal. Dirk Bogarde gives an extraordinary performance as Melville Farr, a compromised QC-in-waiting, as he navigates the murky streets of London, held captive by a photograph of him and a would-be lover crying together in a car. What's remarkable about the film is how, for the first time, it brought such a compassionate and tender representation of homosexuality to British screens; showcasing gay men as victims of a punitive law, rather than criminals seeking to thwart it.

Much has been said about the film's role in decriminalizing homosexuality (Lord Arran, the chief architect of Britain's 1967 Sexual Offences Act, wrote personally to Bogarde to thank him for his portrayal of Farr), and Victim stands as testament to the power of cinema in changing public and parliamentary opinion. If nothing more, the film is a timely reminder of how far society has progressed, while also an indictment of how much is still to be done.

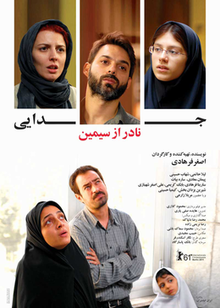

Asghar Farhadi's A Separation (2011)

Becoming the first Iranian picture to win an Oscar, Farhadi's film follows a morally taut line of inquiry, using the framing of an initial divorce hearing to chart the complex territory of religion, class, and gender in contemporary Iran. Living with an ailing father and a conscientious young daughter, a husband and wife seek a divorce over their irreconcilable views on relocating abroad.

Becoming the first Iranian picture to win an Oscar, Farhadi's film follows a morally taut line of inquiry, using the framing of an initial divorce hearing to chart the complex territory of religion, class, and gender in contemporary Iran. Living with an ailing father and a conscientious young daughter, a husband and wife seek a divorce over their irreconcilable views on relocating abroad.

An initial hearing, told directly to the camera, challenges the audience to make a nuanced judgment on the ambiguity of what's right and wrong, with no definitive answer. Further events bring only more confusion, alongside a cast of characters all riddled with more moral and religious complexity.

With an intricacy of plot and deftness of touch, this delicately compassionate study offers a stunning interrogation of the incompatibility of the law's letter and the law's spirit. In highlighting the conflicts between the rigidity of regulation and the fluidity of human nature, the result is a profound and impeccable cinematic achievement.

Distributed by Sony Pictures Classics (US)

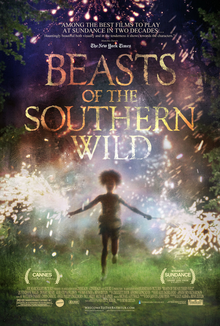

Benh Zeitlin's Beasts of the Southern Wild (2012)

Both an arresting and beguiling dreamscape, Zeitlin's debut feature is a masterful foray into a world of magical realism. Anchored by a revelatory performance by six-year-old Quvenzhané Wallis (what were you doing when you were six?) the film follows a cohort of people living in an abnormal but joyous community known as the Bath-Tub. Exquisitely played by Wallis, Hushpuppy and her father navigate this united community before a storm (and societal forces) plague their previously harmonious ways of living.

Both an arresting and beguiling dreamscape, Zeitlin's debut feature is a masterful foray into a world of magical realism. Anchored by a revelatory performance by six-year-old Quvenzhané Wallis (what were you doing when you were six?) the film follows a cohort of people living in an abnormal but joyous community known as the Bath-Tub. Exquisitely played by Wallis, Hushpuppy and her father navigate this united community before a storm (and societal forces) plague their previously harmonious ways of living.

Unshackled from the conventions of federal jurisdictions, folks in the Bath-Tub are entirely governed by communal connections and self-devised laws of preservation and understanding. Though they live in poverty, Zeitlin chooses to celebrate the wealth of his characters' spirit. And instead of portraying a community held inert by the dream of a better tomorrow, his character sketches are immersed in the beauty of today, by the beauty of the now. It is perhaps the most left-field recommendation on the list, but Beasts is nonetheless a captivating window into a self-governed community demonstrating adelicate dance between the reality of truth and the power of hope.

Theatrical release poster shown above - produced: Cinereach - distributed: Fox Searchligh Pictures

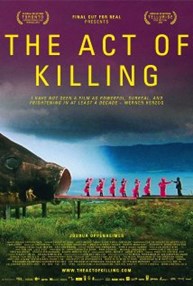

Joshua Oppenheimer's The Act of Killing (2012)

Joshua Oppenheimer's seminal documentary is at once unpleasant yet entirely necessary viewing. Documenting the cultural and psychological legacy of the government-sponsored Indonesian genocide of 1965, Oppenheimer's film is an unprecedented cinematic endeavour, showcasing a society living with, and living through, decades of sustained propaganda and impunity.

Joshua Oppenheimer's seminal documentary is at once unpleasant yet entirely necessary viewing. Documenting the cultural and psychological legacy of the government-sponsored Indonesian genocide of 1965, Oppenheimer's film is an unprecedented cinematic endeavour, showcasing a society living with, and living through, decades of sustained propaganda and impunity.

Using a kaleidoscope of film-making techniques, Oppenheimer allowed a handful of perpetrators to re-enact their killings - what transpires is a lucid merging of fact and fiction. The result is a fascinating demonstration of how an unresolved history still riddles a contemporary context in desperate need of reconciliation. Undoubtedly, this is documentary film-making of the highest order.

Theatrical release poster shown - produced: Final Cut for Real DK

Andrew Zvyagintsev's Leviathan (2014)

In less capable hands, Zvyaginstsev's critically acclaimed drama would have strayed into sermon, becoming a heavy-handed depiction of 'the powers that be' arranged against 'the powers that aren't'. Instead, the film is an elegant and sprawling testament to an average man squeezed by a state's domineering reach. With novelistic clarity, the film follows the unraveling of Kolya, a small-town man, as he attempts to block a corrupt political chief from seizing the beautiful piece of land his family call home. Seeking counsel, Kolya looks to a solicitor friend in Moscow, and together, they wade through a bureaucratic system with devastating consequences.

In less capable hands, Zvyaginstsev's critically acclaimed drama would have strayed into sermon, becoming a heavy-handed depiction of 'the powers that be' arranged against 'the powers that aren't'. Instead, the film is an elegant and sprawling testament to an average man squeezed by a state's domineering reach. With novelistic clarity, the film follows the unraveling of Kolya, a small-town man, as he attempts to block a corrupt political chief from seizing the beautiful piece of land his family call home. Seeking counsel, Kolya looks to a solicitor friend in Moscow, and together, they wade through a bureaucratic system with devastating consequences.

Despite winning universal international acclaim, the fact the film was heavily divisive in Russia speaks to the culture wars still dominating the country's political discourse. Regarded as “enemy-of-the-state propaganda” by some senior officials, the film's backlash draws focus to a society fraught with regulation and offers a window into a world where art remains heavily contentious.

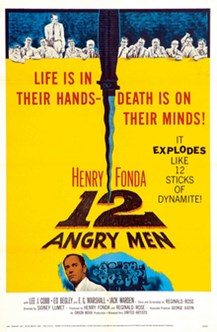

Sidney Lumet's 12 Angry Men (1957)

And finally, with everything already written, what's there left to say?If you've seen it before, see it again. And, if you haven't, let your eyes be opened to Sidney Lumet's timeless classic. Dubbed a “masterpiece of stylized realism,” the film follows twelve jurors as they hash out the details of a murder trial with a seemingly forgone conclusion. Pigeon-holed by a presumption of guilt, all but one of the jury members – played marvelously by Henry Fonda – stands up for the virtue of reasonable doubt.

And finally, with everything already written, what's there left to say?If you've seen it before, see it again. And, if you haven't, let your eyes be opened to Sidney Lumet's timeless classic. Dubbed a “masterpiece of stylized realism,” the film follows twelve jurors as they hash out the details of a murder trial with a seemingly forgone conclusion. Pigeon-holed by a presumption of guilt, all but one of the jury members – played marvelously by Henry Fonda – stands up for the virtue of reasonable doubt.

With moistened brows and shirt sleeves rolled, the palpable concoction of humidity and justice is deliberately confined to the four walls of the deliberation room. And as the arguments ensue, with the weight of morality mounting, watch as the camera increasingly pulls us closer and closer, until we're seated alongside Lumet's cast, rubbing shoulders with tension and testosterone, and witnessing one of the finest displays of justice-in-action cinema has ever seen.

What books do the managing partners of law firms read? Find out here.