It's never too early to start thinking about the big picture. Between in-house, government, and partnership, there are huge decisions to be made. Recruiters at Lateral Link give us some advice on where to start...

Wait! Don’t run away quite yet. We know how stressful the title sounds and know you have no shortage of decisions to make. No matter what stage you’re at – thinking about OCI or your next career move – we at Chambers Associate don’t want to add to your already overflowing plate; we’re here to help finish your leftovers when you’re full! So, pass us the metaphorical brussels sprouts and mushrooms (a matter of personal preference, really), because we’ve got a full tasting menu to map out some of the options you might’ve been weighing up, or help you consider others that may not have crossed your mind at all. Chicken or beef? Tofu or vegetables? In-house or government? Equity or non-equity partnership? If you’re at a crossroads for whatever reason, don’t panic. Enter Lateral Link’s Buddy Broome, Summer Eberhard, Ata Farhadi, and Nick Pappas, a team of expert recruiters with heaps of industry knowledge to serve you on a silver platter. Hope you’re hungry!

Keeping It Simple

Making partner, going in-house, or transitioning into government is all well and good in theory, but do you know what that actually means? We’ve asked our interviewees to break it down and explain it like we’re five years old; they helpfully obliged. Let’s start with becoming in-house counsel. “Working at a law firm, you have multiple clients,” principal Ata Farhadi starts, “working in-house at a company, you really only have one: the company you work for.” Of this, Buddy Broome, director, notes, “Your role depends on the size of the company. Some companies only have one in-house counsel where they do everything: review contracts, enter into leases, help manage litigation, and advise the company on what to do.” The bigger the company, the bigger the in-house legal department. Principal Summer Eberhard elaborates, “Typically, the companies that have robust legal departments are fairly large that have many different types of roles that focus on – for example – privacy or employment law or corporate transactions.” Eberhard states, “If it’s an attorney’s goal to end up in-house, these roles touch a range of industries - everything from start-ups or large tech companies to non-profits - they often have a whole in-house legal department.”

“If it’s an attorney’s goal to end up in-house, these roles touch a range of industries..."

What about the government side of things? “Going to work for the government means you are employed by the federal, state, county, or city level government,” says director Nick Pappas. And of partnership? “Being on the partner track means that, first of all, you’re an associate or counsel at a law firm who’s working towards becoming a partner in a law firm,” Pappas continues, “becoming a partner means you are either an equity or non-equity partner.” Equity partnership is less common, “as it usually takes longer and is determined by the size of a lawyer’s book of business,” Pappas caveats. More on books of business later, though. Before moving on, we should note that these aren’t the only options available. It’s your career and you’re at the helm of the ship; you’re free to steer it in whichever direction you want, but these are the most frequented career paths for attorneys. So, now that we have the plain-and-simple explanations of what it means to become a partner, move in-house, and work in government… how do you decide which one is right for you?

Considering Your Course of Action

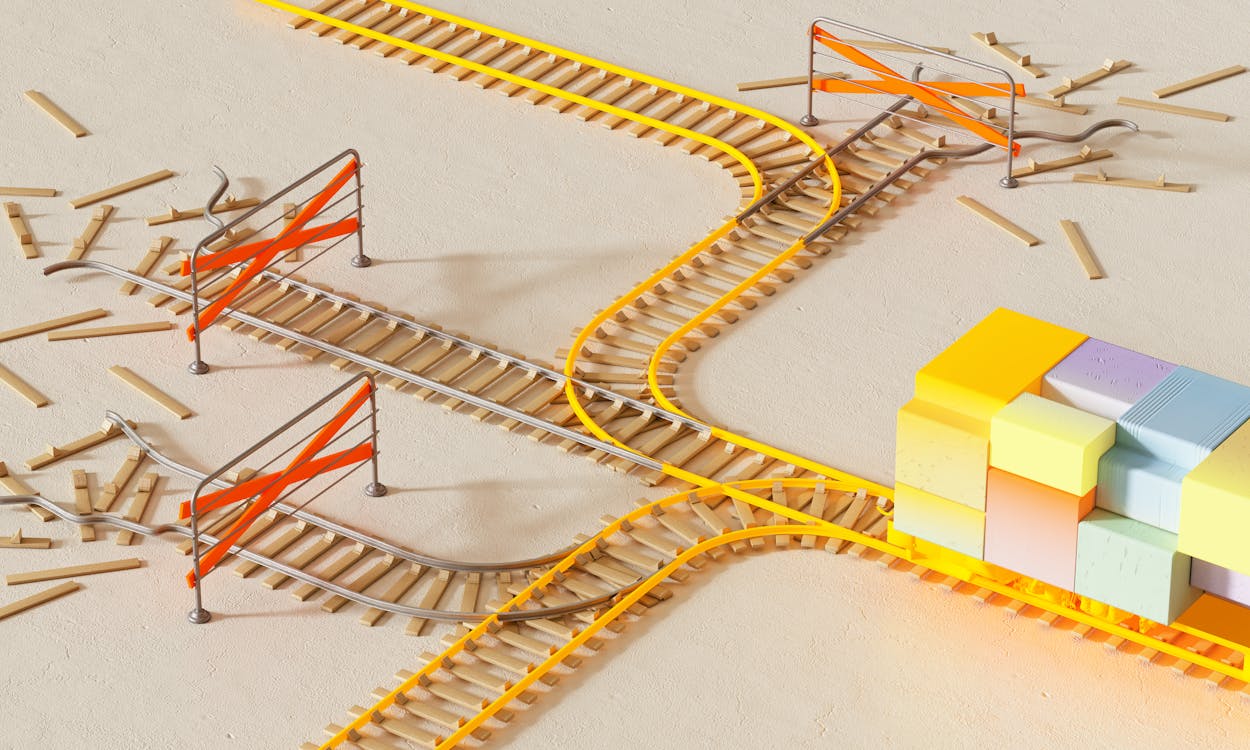

There are countless things to consider before settling on a long-term career choice. It takes time and there’s no wrong choice. It starts with deciding what matters to you most, as there are differences between each path. Broome likens it to a “Choose Your Own Adventure – when you make one decision, it impacts the next decision that you’re able to make.” Essentially, if you’re going down Route A, it’ll be harder to get to Route B. “It’s like a tree branch, the more the branch grows in one direction, the further it divides from the rest of the tree,” Broome synonymizes again, so “the sooner the attorney thinks of what they want to do with their career, the easier it is to get there.”

Partnership “starts from day one,” Pappas begins. No seriously – the most important thing for young associates to keep in mind if they’re looking to make partner is “their reputation.” It sounds ominous, but it’s no joke; “reputation is usually comprised of several components,” Pappas divulges, “the top of which is producing elite work product. If you’re going to be a partner, 99% of the time, it’s going to start with you creating phenomenal work product and getting stellar results for your clients.” He breaks this down even further, sharing that reliability should be front of mind for juniors, because, when you’re junior, “you don’t have the substantive knowledge that you gain from practical experience. What you do have is energy and time.” To make partner, you will have to “throw yourself into the work to ensure that you’re the person who the partners come to when they need something done. That way, you become an indispensable part of the team.” Farhadi echoes this sentiment, adding, “You have to execute tasks at a rate that is often quite difficult. The average hours that some firms expect is very high, and they expect their associates to prove that they can just get through that before any other consideration.” He placates, “It can be very difficult, so I don’t hold it against anyone who feels like it’s not for them.”

These have to be actions you’re ready to take, but hard work pays off, as Broome tells us: “As a partner, there’s more autonomy and control over your career.” He continues, “If you’re a partner with a portable book of business and you want to move firms, you have more opportunities to do that because you’re a revenue generator, and that's very coveted.” Firms will always need people to bring in money, which makes the difference between being a revenue generator and a cost center a key consideration when it comes to making partner and moving in-house respectively.

"We know many people who’ve gone in-house and feel like they’ve worked harder than they have at law firms.”

On the topic of moving in-house, when asked why attorneys gravitate towards working as counsel, Farhadi cites hours as a primary consideration: “People seem to think going in-house means they won’t be called upon at odd hours or won’t otherwise be burdened as a consequence of excessive hours. Oftentimes, that’s not the case,” he laughs, continuing, “the state of the company you work for – depending on where they are in their growth trajectory – can mean that there’s a lot to do. We know many people who’ve gone in-house and feel like they’ve worked harder than they have at law firms.” It’s not necessarily an incorrect assumption though, Farhadi says, but “it’s certainly not a panacea if you’re looking for fewer hours. That’s not to say that you can’t find something where it is like that, of course. Just keep your eyes open.” Broome provides a positive counterbalance to the long hours: “One pro of going in-house is that you don’t have billable hours. You also get an opportunity to do something outside of law where there’s room to advise, be part of the corporate structure, and attain corporate leadership.”

Pappas puts another reason on the table: “The draw is working for one client as opposed to many.” Why is that a good thing? “If you’re at a law firm, you’re servicing a large milieu of clients,” he explains, “In-house, you only have the stakeholders at the company.” As in-house counsel, “you’re going to have to wear more hats than you would at a law firm. You can be handling a labor and employment issue one day, advising on a real estate issue the next, or giving advice on a term in a contract another day.” The size of the company you’re looking to work for is a consideration here too, as “if you’re going to work in-house, you need to have a look at the breadth of the position that you’re going to be taking up,” Farhadi advises. He goes on to say, “The broader it is and the more overall responsibility you have, the better.” This isn’t just because you want to keep busy, but because “it’s harder to climb up the ladder when you’re in-house. Going in-house isn’t a monolithic experience, but where you slot in or start tends to affect the rest of your career,” Farhadi warns.

There are drawbacks to going in-house, as Pappas mentions: “On the negative side of the spectrum, if you’re at a company that doesn’t value its in-house lawyers, the business team can look at the in-house attorneys as a cost center, whereas at law firms, the lawyers are profit generators; this dynamic can really impact a lawyer’s work and create stress.” This shift in dynamic can be “jarring to people when they make the transition,” so Pappas similarly cautions that “if you’re looking to go in-house, that’s something to really consider and think about.” Broome agrees, adding that “there’s a little less stability because if you decide that you would like to move to a different company, the options to stay in your area of practice or geographic location are much more limited.”

"You're making a difference... public service can be very fulfilling and satisfying in ways that private practice cannot."

In a government role, “there are several different factors that draw lawyers to this sector,” Pappas reflects. Depending on your chosen area of practice, “you can see an improvement in your lifestyle compared to working at a law firm; you usually have more regular hours and maybe more flexibility in the government.” Even better news, Pappas tells us that government jobs “tend to have more stability than in-house or firm jobs because lay-offs and firings occur less frequently. Now, that’s not always true, but it often is.” Other than the appeal of a clearer work/life balance, there’s also the opportunity to become “a subject matter expert,” he continues; for example, if you’re an attorney and you join the Securities Exchange Commission, “you’ll be focusing on enforcement actions and other securities-related matters. If you join a district attorney’s office, what you’ll get there is trial experience.” Pappas also points out the added benefit of feeling like “you’re making a difference,” because “public service can be very fulfilling and satisfying in ways that private practice cannot.” It almost sounds too good to be true, so… what’s the catch? “The compensation is usually much lower than it would be at a law firm,” he admits.

Making Your Money

Money is a big driver here, especially since life tends to come at you fast. Between student loans, childcare costs, and getting on the property ladder, you want to be making enough money to do it all without having to burn your candle at both ends. “At most BigLaw firms, the compensation is what it is,” Eberhard states, “It’s a lockstep model. Middle market firms compensation is often a little below that, but it is still competitive.” Get this, though – “Compensation at law firms has increased several times since 2020,” she recalls, “In-house compensation has not increased at the same rates, so the delta is wider than it has ever been.” So, Eberhard finds that fewer associates want to go in-house because “the impact it would have on compensation, particularly at the more senior levels, would be too much for their financial situation.” As Broome puts it, before deciding to leave a law firm, “every person must answer the question for themselves: ‘Can I afford that move?’”

With government roles, it’s much of the same – “while compensation in government roles has always been less, the increase in BigLaw compensation has caused associates to take a closer look at whether the move is right for them,” Eberhard nods. If you’re curious about what compensation looks like in a government role, though, you can find out; “the pay scales of government jobs are all public information,” Pappas informs us, so “you can find that information online to get a better sense of where you are in the compensation bands and the years of experience that it will take to get to the different bands.”

"Each of these paths has great compensation! You're making more than what the average person is making."

Nobody wants to hear that they’ll be taking a pay cut but look at it the way that Eberhard does: “each of these paths has great compensation!” She reminds us that in these roles, “you’re making more than what the average person is making.”

Picking Your Practice

Just as important as monetary motivation is picking a pertinent practice area that aligns with your future ambitions. “What you specialize in has a real impact on your future trajectory,” Farhadi informs us. Some practices lend themselves to in-house or government roles, as Broome shares, “If your goal is to go in-house, your route – typically – is to go down the transactional route, whether that’s doing corporate, M&A, real estate,” so litigators beware: “it’s more challenging. Fewer companies bring in litigators to be their in-house counsel,” Broome forewarns. Eberhard similarly informs us that the earlier you think about your practice, the better, although “I generally don’t recommend lawyers to go in-house straight out of law school or in their first couple years of practice.” Why? “Law firms are there to service their clients and develop good lawyers to do that,” she rationalizes, “that’s their job. Companies on the other hand are there to focus on what the company does and not solely to develop good lawyers; it does not serve their interests in the same way it does a law firm.” Firms tend to “invest a lot of money in training and mentoring,” while in-house career development opportunities depend largely on the type of company you work for. Companies will want you to have more experience and skills from the outset so that you can hit the ground running.

“What you specialize in has a real impact on your future trajectory."

Pappas emphasizes this point, providing some sound advice: “You need to focus on a particular industry, and certain practice areas do have better off ramps into the corporate world,” he confirms, “this is region-specific too.” Say you want to go in-house at a tech company: “It will behoove you to be working where a lot of tech companies are,” Pappas suggests, “in the United States, that’s San Francisco and Silicon Valley. So, if you build relationships servicing tech companies, there are different areas – IP, tech transactions, ECVC – that can facilitate creating good relationships with existing clients. Once you have a relationship with a few clients, you can start networking with those clients to land yourself a job.” That way, you become more marketable because you’ll have “expertise that you can pitch to a company, a track record to back it up, and people to vouch for you,” Pappas advises.

He goes on to address transitioning into a government role. Putting it simply, “if you’re going to go to the government, you’ve got to be doing what the government is doing; that’s, for the most part, litigation.” He mentions white collar, antitrust, environmental securities, and other regulatory types of practices as good gateways to government. With any of these specialties, Pappas notes that with government, you should have a plan before you leave your firm. “If you were in BigLaw and you made enough money to pay off your student loans or get a different experience in public service, that’s something to know,” he tells us, “But if you want to go into government work with the goal of going back to partnership, you’re going to want to look into the highest levels of practice – probably white collar, antitrust, or similar practices at the Assistant US Attorney level because BigLaw clients will pay for your knowledge and experience later down the road.”

Building Your Book

When we asked what juniors can be doing to ensure they’re on track, the answer among our interviewees was unanimous. “Be conscious from the beginning of the importance for you to have a portable book of business,” Broome iterates, which he admits is “hard at the beginning of your career because you are busy learning the practice of law.” We’re here to fix that.

Farhadi sheds some light on perspective when it comes to book building. “You can look at business building as a connections-based enterprise,” he notes, “First start by making a good impression on the most important client you’ll ever have: the partner who is supervising you. Then, as you begin to make a good impression, that partner or the several you work for will start to put you in front of clients and get your name out there.” He boils this down to trustworthiness: “If people can rely on you, they trust you. That obviously involves them identifying with you in some way. They know that you offer them a good service; you have the amiability, the personality, the drive and judgment in their estimation to handle business appropriately. Then, you will begin to become a target of business,” he affirms. Eberhard confirms this, stating that “you have to go through that process of building and maintaining good relationships over a long period of time. If you don’t start this process over your first six to seven years of practice, it’s harder to start doing it out of nowhere.”

"...a lot of lawyers don’t like doing sales, but it’s crucial to building a book of business; people can’t hire you if they don’t know what you do, and they don’t know you.”

Outside of the firm, we were told that juniors must “get out there, meet with people who could hire you, and network,” encourages Pappas, “That’s sales, and a lot of lawyers don’t like doing sales, but it’s crucial to building a book of business; people can’t hire you if they don’t know what you do, and they don’t know you.” For our more introverted readers, this shouldn’t care you off – there are many ways to go about this, and one of them is writing. “Writing articles about your interests in law and how it applies to your clients is a great way to do it,” Pappas explains, “You can do it from the comfort of your office and share it on LinkedIn or other platforms, and that can create some energy and traction for you.”

Admittedly, it does sound like a lot of work, but the importance of building a book ultimately “gives the attorney greater autonomy, greater chance to make partner, and greater chance to earn a higher compensation.” Broome comments. “Look at the big picture: at certain firms, it’s very hard to get a portable book of business because your current firm and your potential clients would not be a good match,” he supplements, “For example, you might be networking and have a lot of potential clients, but your firm’s bill rates are $1,500+, and not a lot of clients can spend that much money for legal services. Conversely, your firm might have lower bill rates, but not have the platform to service the clients that you can bring to the firm. It is important to be aware of whether your firm is a match for your potential clients.”

We should make one thing clear though, as Eberhard is quick to point out: “You can make partner without a book of business!” In fact, “most lawyers that make partner don’t have one, but one of the considerations is often your ability to do business development, firm citizenship, and the quality of your work. By no means do you need to have a $3M+ book of business,” she reassures.

Working with a Recruiter

We know we’ve given you something of an information overload but stay with us! Our experts have got some parting advice about how they as recruiters fit into all of this. “For associates, it’s beneficial to talk to recruiters early – and when I say early, I mean first year,” Broome says, as it helps to have “a recruiter who has known you for a long time and feels that they can really speak on your behalf and advocate for you because they know you,” details Farhadi. What this prevents is you “coming to them in an hour of need and asking a recruiter to expend all their collateral on you” when they don’t know you that well. Obviously, “a good recruiter will take what they’ve got and try to find out as much information as possible to see how they can help you,” but “it’s much better to have a long relationship with a recruiter.” Discussing what your career is going to look like “with someone who has seen a lot, who’s seen how careers go, gives you a lot of benefits because we are able to look at things from the 30,000-foot view,” Broome describes, “There’s a level of trust there. The candidate wants to know that the recruiter that they are working with knows what they are doing and is working in the candidate’s best interest.”

“A good recruiter ends up being a broker..."

What other qualities does a good recruiter bring to the table? “Insight into the market: what firms are looking, what firms might be open to opportunistically hiring you,” Pappas lists, “They also have the nuts and bolts of different opportunities: what are the hours; what is the compensation; what’s the upward trajectory; what’s the culture? They can answer those questions in a way that you wouldn’t be able to figure out just by Googling.” Keep in mind as well that “the best recruiter for you isn’t necessarily going to be the one that calls you with the job you like right off the bat,” Farhadi reminds us, “But I think it’s always ideal to work with one recruiter who has shown you that they are willing to invest in your career move.” Ultimately, “a good recruiter ends up being a broker – introducing you to people you wouldn’t otherwise meet or arranging an introduction in a way that’s more advantageous to the candidate,” Pappas sums up.

And it’s never too early to start thinking about these goals and speaking to a recruiter either, as Eberhard puts it in perspective: Broome concurs, telling us that “it’s beneficial even as a first year to just have a conversation with us so you can figure out what it is that you want in five, ten, twenty years down the road from now and what is the best route to get there.”