Over 3,000 junior associates told us about D&I culture in their law firms. We examine what the trends mean for law firm retention and the individual's career.

Antony Cooke, June 2020

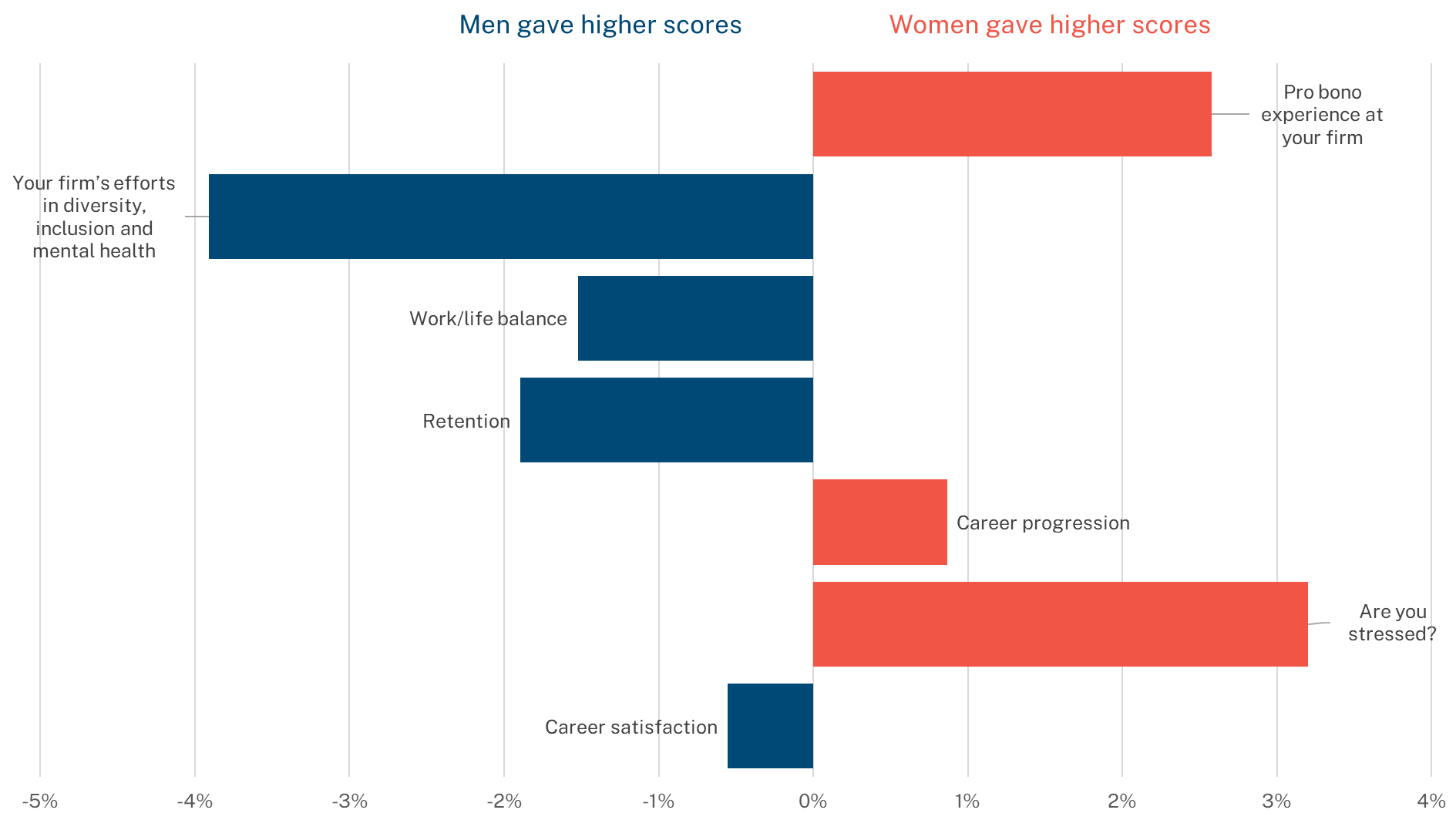

MEN and women consider themselves fairly equally happy in their jobs in their top law firms. But the graphic above shows how the two sexes diverge on some fundamental areas: most notably diversity and inclusion policy and culture. In general, men hold a more positive view of their firm's performance on D&I; the assumption is that men are less critical because they are less personally affected by it or are less aware of its failings.

A story begins to build from the moment men and women join their firms: opportunities and experiences are not equal.

Men also claim better work/life balance and feel their firms are working to retain them more than women, while women experience more stress. A story begins to build from the moment men and women join their firms: opportunities and experiences are not equal.

Over 3,000 junior associates (1st, 2nd, 3rd and 4th years) across US BigLaw responded to our questions about every aspect of their lives in their firms and their career aspirations. This report focuses on the divergence between men and women in the survey. We examine other strands of diversity elsewhere on this site.

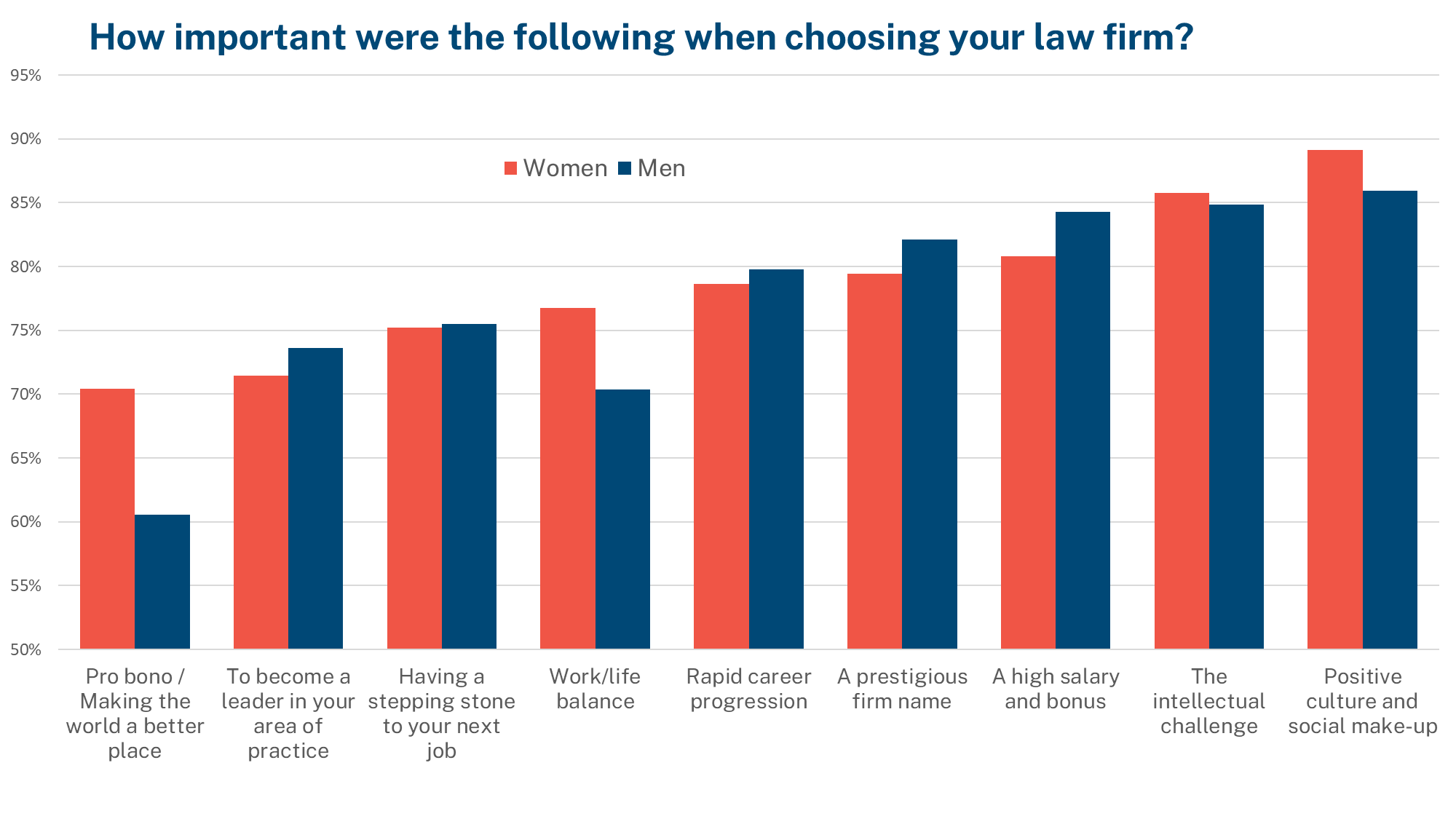

We asked associates what was most important to them when joining their firms. For the second year in a row, both men and women are seeking a 'positive culture and social make-up' more than any other career goal. Does reality meet expectation?

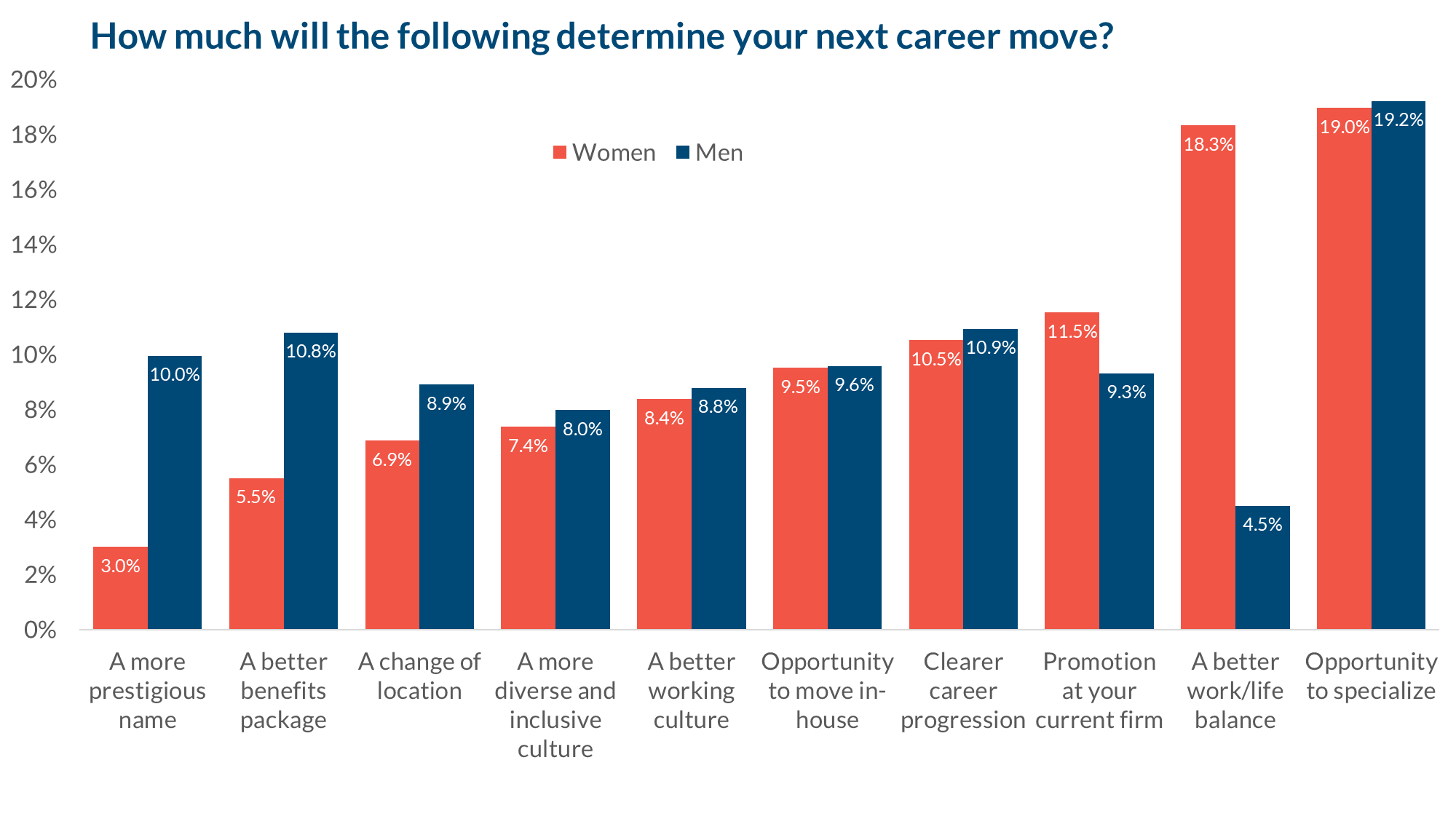

As soon as lawyers gain a few years' experience, their priorities begin to shift. As we learnt above, men and women undergo different experiences at their firms, which nudge their careers in different directions. Men become more motivated by earnings and prestige, while women seek a better work/life balance. In a profession as uniquely pressured as the law, answers and action are still not there on making it compatible with a society that continues to place the larger burden of parenting on women. The current solution for parents, as we can see, is to find a firm or in-house role that will be more accommodating. And this is where the gender pay gap begins in the law.

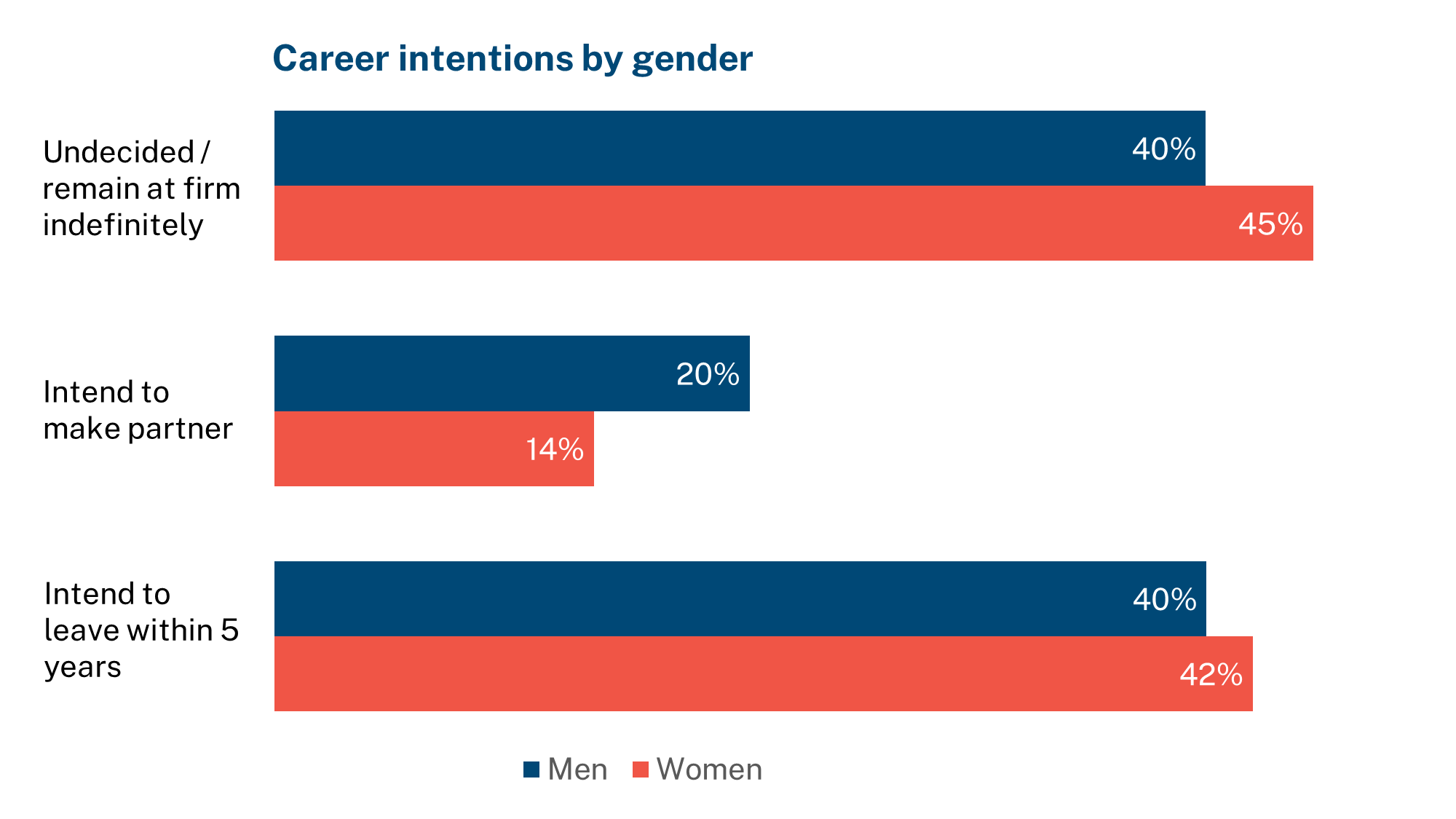

The future pay and opportunity gap becomes more starkly visible when we asked both sexes about their commitment to their law firms: men are more likely to aim for partnership from the get-go.

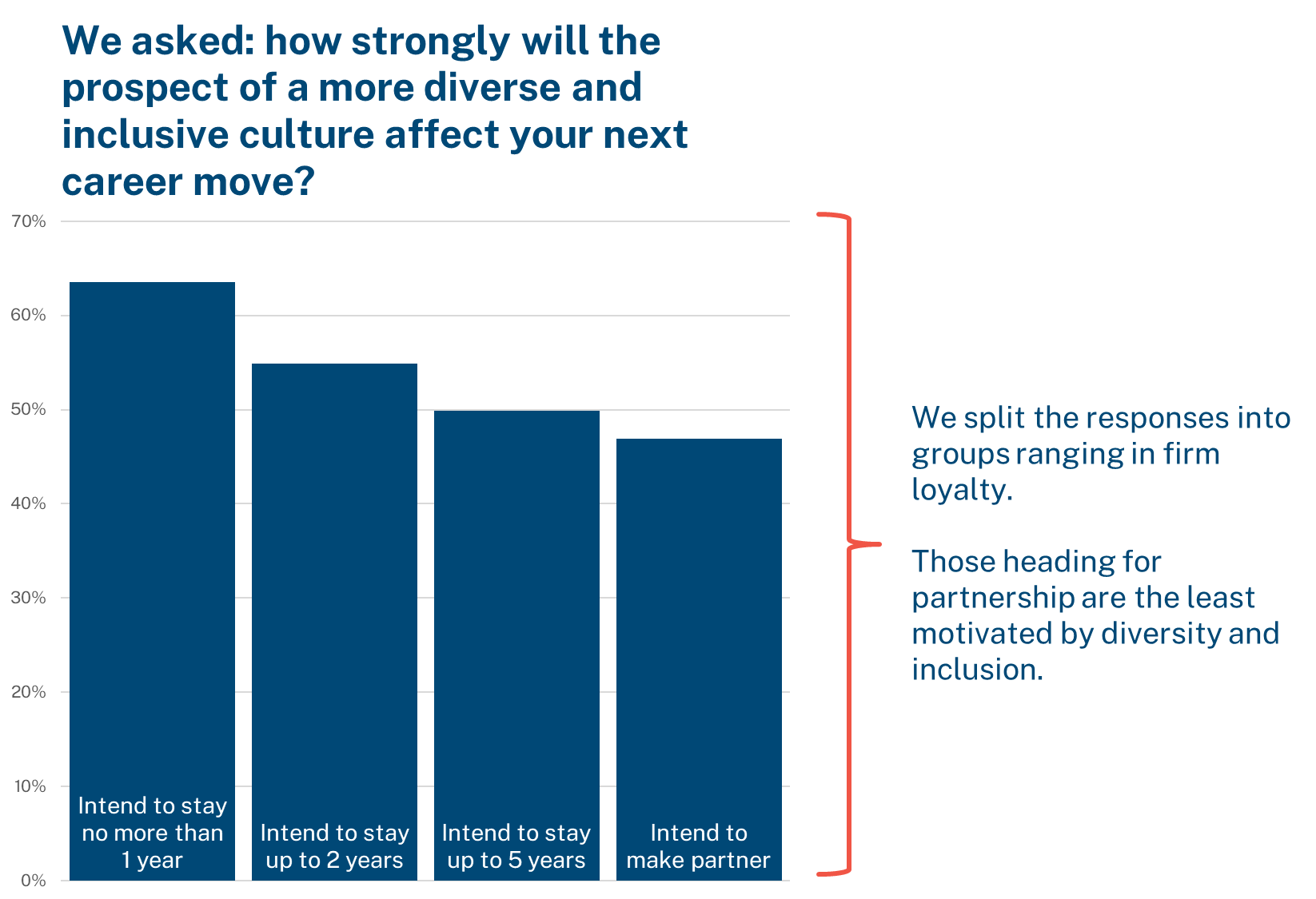

'those least interested in D&I policy are the most likely to become law firm leaders.'

Why men are more likely to head for partnership than women is down to the many cultural factors that define the lawyer's experience, affording one sex more entitlement, opportunity or certainty than the other. It's the job of law firm D&I officers to address this: to make sure hiring, mentorship, training, affinity groups, work allocation, assigning credit, and promotion opportunities are robust enough to counter the trends we see here. The clear message is the initiatives are still falling short – or that the structures they're seeking to dismantle are too strong.

We found that D&I policy plays a crucial role in lawyer retention, and that those least interested in D&I policy are the most likely to become law firm leaders.

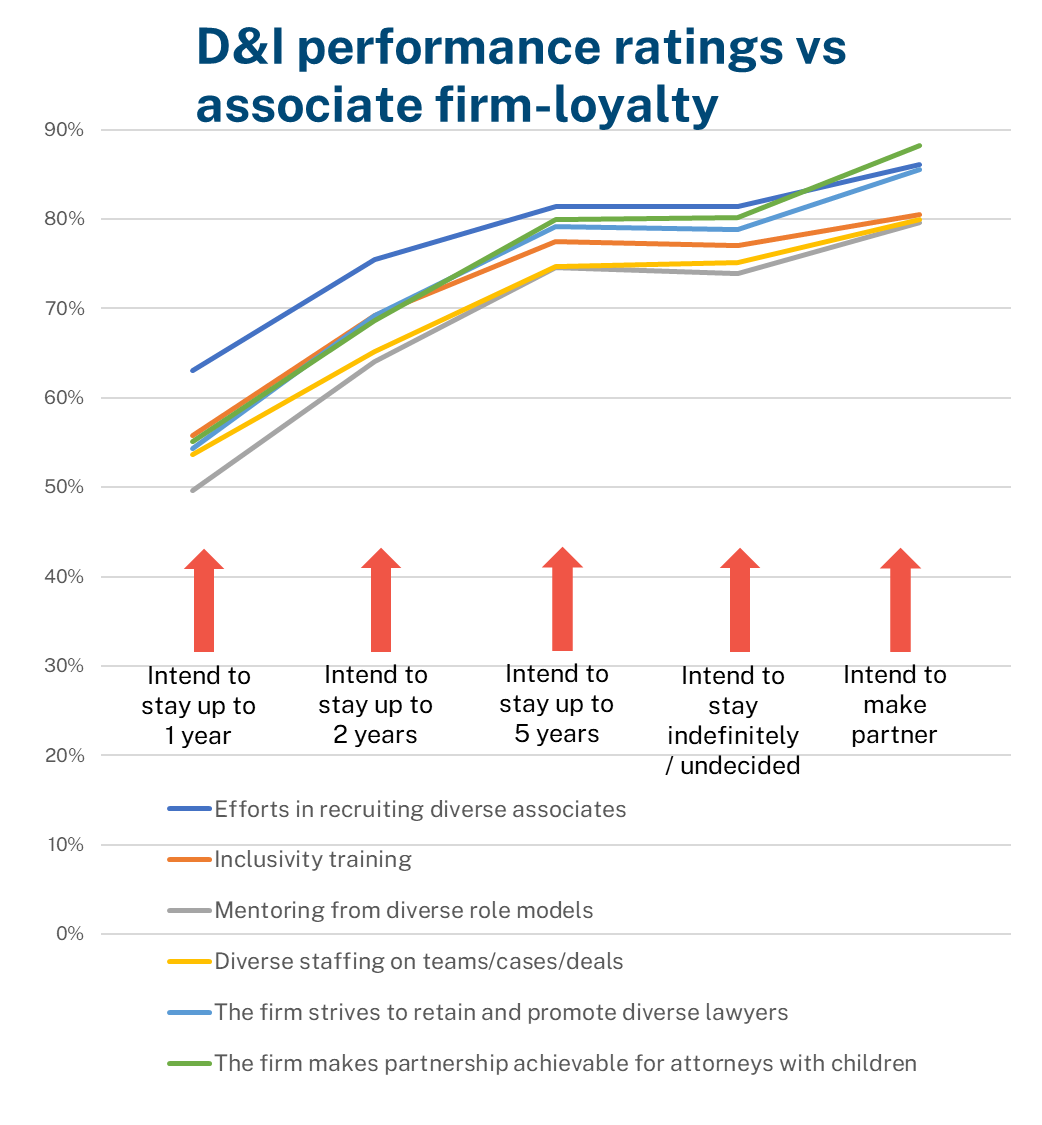

We drilled down further on this topic and looked at the activities in law firms that define good and bad D&I culture. Associates rated their firms on all the questions below, and we split the responses up by how long those associates intend to stay at their firms. The results showed a familiar picture of those most affected by poor D&I culture wanting to leave their firms, and those who are the least critical of D&I policy – or least affected by it – gunning for partner. One of the greatest obstacles D&I departments face in their implicit bias training is achieving partner buy-in.

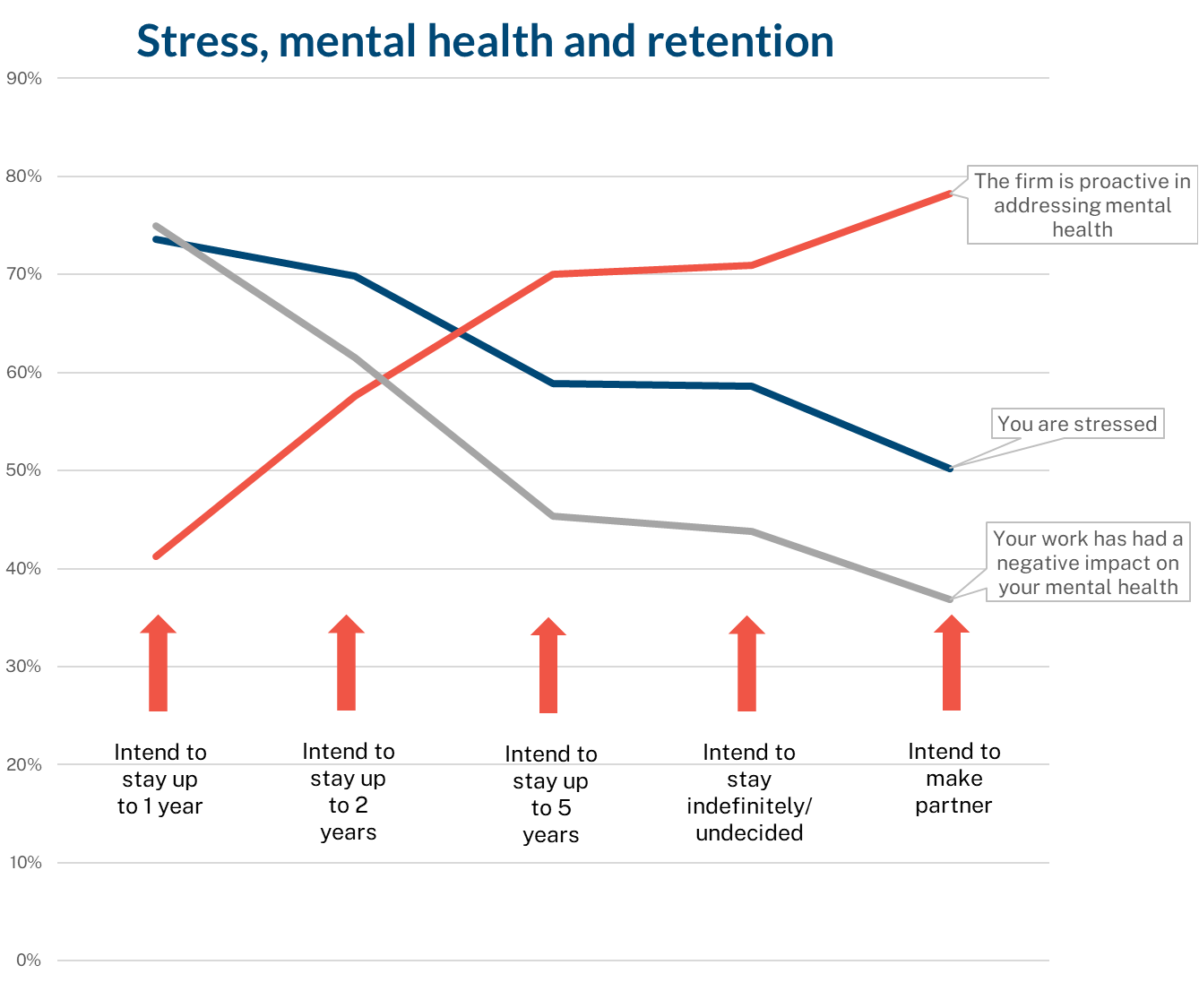

We did the same analysis on the topic of stress, mental health and retention and found that similar correlations occur. The BigLaw economy dictates that hours are long, expectations are high, and so stress and mental health are pervasive issues. Acknowledging the pressures of the profession is the first step to retaining talent. We see below that if a lawyer is stressed and the firm does little about it, they will leave.

Attrition costs law firms millions. Consider how much they invest in onboarding and training talent, and then how much of that goes to waste when lawyers leave in the first few years, and the firm has to spend again on lateral recruiting fees. As we saw earlier, D&I culture may not grab the attention of those aiming for partnership in the same way it does for most associates, but you'd think law firm leadership might at least find its impact on the bottom line alarming. Firms should be aspiring to something far better than economic efficiency, however: the business case for diversity is old news. And as we can see playing out in the stress graph above, the economic model of BigLaw is the problem and fundamental to all the issues explored here.

When students enter the market, what they want most of all from their firms is a 'positive culture and social make-up', and only a fraction of associates have their expectations met. Over the course of a decade we've seen firm culture gradually rise in importance to students and associates, while the more traditional signifiers of success – status, power, earnings – have given way to it. This mirrors a generational trend we’re seeing of questioning established behaviors and calling out cultural anachronisms. Millennials and Gen-Z are going to do things their way. At Chambers we also hear from thousands of law firm clients and their views are beginning to echo those of the students: that culture is a deciding factor when selecting a law firm, and D&I achievements are pivotal to that. This is the bottom line.

Learn more about our research in diversity and inclusion

Learn more about our research in diversity and inclusion